Steep Learning Group are Filip Tyden, Erik Hedman and Alex Webb—three London-based rock-climbers who each approach the outdoors from a fresh, left-field angle.

Whether they’re making jigsaw puzzles of infamous boulder problems, or photographing their adventures from a fresh, modern perspective, their work pulls from far beyond the climbing realm—merging a distinct DIY approach with a clean and considered visual style.

We caught up with them to talk about how they met, what they do and the importance of keeping things vague...

Starting at the beginning, how did you all meet?

Alex: Erik and Filip have known each other for years. They went to art school together and then worked together—they discovered climbing a few years before lockdown, then during lockdown they realised they wanted to move their art direction more into the outdoor realm. In lockdown all the London climbers started climbing these two boulders—one in Shoreditch Park and one in Mabley Green. Out of curiosity they got in touch with John Frankland, the artist behind the sculptures, and found out more about the history of them.

Erik and Filip collated all the different problems that people had done on the boulders, and they put together this guide. I got in touch with them after seeing it on Instagram. I was a bit late to the lockdown London boulder party, but I was intrigued by what they were doing—the aesthetic was really interesting, and it didn’t feel like anything anyone else was doing in relation to climbing. Subsequently these guys started making t-shirts and chalk bags, and approached me to do a little shoot. And then we moved into a studio together shortly afterwards.

Why was it that you all gravitated towards climbing in the last few years? That seems like quite a common thing.

Alex: I was brought up with climbing through my dad. I’d gone to the climbing wall a lot when I was quite young, and then I gave up on it when I was a teenager. I came back to it maybe seven years ago—so whilst I have a history of it, I have also come back to it at a time when it’s definitely on the up. I can’t say exactly why more people are climbing again, but I think fitness and wellbeing are definitely on the agenda.

Erik: I think bouldering has also made climbing more accessible in general, with lots of gyms popping up, a friendly vibe and a low threshold to get started. It’s similar to what happened in skateboarding when miniramps and smaller obstacles came along as options to big vert ramps.

Yeah, I suppose it’s like an 80s vert skater having to get padded up and find a ramp, versus a street skater who can go anywhere. Bouldering doesn’t require much.

Filip: Skateboarding is really hard. Nobody can just pick up a board and do what you see on TV. But with climbing everyone kind of knows how to climb—it’s a natural thing. And then as Erik said, they kind of nailed the format with bouldering gyms. It’s so easy—it takes two minutes to explain to someone the numbers and the colours and you’ll be having fun. And you get better quite quickly too.

If I were to take a friend who’s never skated to a skatepark, there’s not much they’re going to be able to do—he’s going to have months of gnarly pain, even just to carve a bowl. We used to skate a lot—and there are some similarities between them. One of the really nice similarities is that you can climb with several people together, even if you’re at different levels, and everyone will get psyched about everyone else’s progress.

Alex: I can’t think of many other sports where you don’t have to rely on other people—and don’t need that much equipment. You can just pick it up and go and do it—and be satisfied quite quickly. Climbing is varied and different, and requires lots of different skill sets. I think a lot of people find it exciting because it’s like going to a children’s playground… but you’re an adult.

It seems there’s a whole new wave of climbers now pushing things in different directions.

Alex: I think climbing is growing exponentially in every direction, but there definitely seems to be a tendency towards people being interested in it as a sport, or from a performance point of view. Whereas my interest in outdoor climbing is more in the adventure stuff, rather than going to a sport crag in Spain that’s really overhung and hard.

Erik: I feel like it’s good that it’s getting big enough to seperate. Like with snowboarding—I think it did it good when it came into the Olympics as people chose whether they’re only going to be interested in doing triple flips in Red Bull caps, or travel around and film interesting stuff—and do new kind of tricks.

It’s almost like everything is splintering off. There’s not just one way to be a climber anymore.

Erik: I think that’s what we’re interested in visually too. We’ve got these boxes of climbing magazines, and it feels like in the 70s and 80s there were maybe 64 companies in Sheffield making climbing gear. And the photography was fun and the ads were fun. There was an independent vibe to everything, and it felt like as time has gone on, everyone has just accepted these big brands—and the ads look the same, and the format is the same. It’s like things had gone single-minded. We want to come in from another perspective and explore what else can be done.

Filip: There weren’t many things in climbing that got us excited in the way that we’d maybe get excited by a skate video we really like. There weren’t many things out there that were doing things differently, so we started the Instagram to put some different things we thought were fun or interesting out there.

Erik: And then we attracted people who had a similar vision. It feels like there’s a small community now of people doing things a different way.

Alex: It’s exciting. Climbing has definitely had that DIY past, but it’s pretty underground and it hasn’t been talked about. It feels nice to be harking back to that, whilst bringing it into a new life. We’re thinking about how to document the outdoors in new and interesting ways—more about the culture and the people and the stories, rather than doing the hardest thing, or going to the most extreme place.

I think it’s nice to hear about what’s local to people too—like the boulders in London were local to us. There are other people in the UK doing similar things—championing their areas. It’s nice that you can go anywhere in the world, and if you find someone who’s into climbing, you’ve got a common ground. Connecting with other humans is a nice, reassuring and fulfilling thing.

Do you think that’s one of the reasons people are getting into these activities again like climbing? As more and more of life is lived on computers, are people realising that there are certain things that these devices can’t replace?

Alex: I think people are becoming more aware of the different kinds of things they can do out there. Because everything is streamlined through a computer, or your phone, they want to go against that—they don’t want to do an activity that’s mediated through an electronic device. They’d rather do something that’s completely removed from it.

Filip: I think more people were getting into the outdoors before covid, but lockdown turbocharged the pace of it. Because you weren’t allowed to do anything, you had to look at what was local—you couldn’t get drunk in a club, or fly, but you could go to the forest. And everyone just started doing it.

You’re pulling in from a wider pool than just climbing. What do you look at for inspiration?

Filip: Everything, in a way.

Alex: My background is photobook publishing, so I was brought up on fine art photography and making books. And then I worked as an assistant for a fashion photographer. And then with being into the outdoors as well, there’s a melting pot. I’ll look at what fashion photographers are doing, and then maybe try and bring that approach into the outdoors—just trying to put a different spin on things.

Erik: We all came from art school—looking at art and design and film, and then there’s skateboarding on top of that. I think skateboarding is one of the few activities that has been living close to art and design for a long time. And maybe it’s something that’s been missing in the outdoor thing—although it did seem that in the 70s they were closer.

Is it important to look outside of the immediate references? If climbing just pulls from climbing, it doesn’t really evolve much. Has there got to be a mix?

Alex: Climbing definitely had that mix, but it’s just not that easy to find. There was a time that climbing was cool in the 80s and early 90s, but then there was a big gap. If you look at the films with Jerry Moffat and Ben Moon, there’s some weird stuff—there’s this BBC thing with Ron Fawcett, and it’s cool—it’s shot in a really different way. Climbing definitely has the history and the culture around it.

Erik: Cycling went through the same thing. There were all those different interesting brands, then it died down when there were those mass produced bikes, but now it’s come back—with different iterations. The industry has shifted a bit, and it’s blossomed out so it’s not just about the Tour De France. I think it’s fun to think that climbing might do something similar—just keep on growing, creating lots of different small worlds.

Definitely. There seems to have been a resurgence of small climbing brands crop up lately. What is exciting at the moment in climbing for you three?

Filip: Some of the things that the people in Sheffield are doing are quite interesting—they’re really good climbers, but you can feel that they’re looking for something different than what people were looking for before.

Alex: It’s splintering. You’ve got professional climbers like Aidan Roberts and Hamish McArthur that are starting their own things. Rather than just being about performance, they’re interested in the culture and thinking about it in different ways. It’s almost like what people are doing in terms of their climbing and their achievements are becoming less important—the interesting stuff is what goes on around that. It seems like in every country there are people taking it into their own hands and creating their own little projects. It’s fun.

Your projects are wide ranging—from clothes to films to jigsaws. Instead of having some mission statement like “We’re a chalk bag company, we only make chalk bags,” it feels like you lot are all over the place—in a good way. Was that intentional?

Erik: I think it’s fun when people don’t quite know what you are.

Alex: Exactly. I like it when things are hard to define, or slightly tongue in cheek.

Filip: We made this jigsaw puzzle using one of the photos that Alex took of a famous boulder—and that was because we thought it was an interesting way to talk about the boulder. It was something we hadn’t seen before.

Erik: And now we’ve heard that the puzzle is actually harder than the actual boulder itself—only two people have managed to finish it so far.

Haha—sounds like quite the challenge. Looking at what you do, it’s refreshing to see something that isn’t so defined—quite often it feels like people turn their passions into a job—almost co-opting the corporate world onto something that’s meant to be fun.

Erik: We’re sadly trained to do that, but I think it’s important to have fun and not to put too much focus on the end goal. My wife climbs with a girl who doesn’t care about the colours of the holds. They’ve told her about them, but she doesn’t care—she just keeps climbing using whatever colours she feels like. And that’s really cool.

I think it’s sad in a way that there are grades in climbing. I think that’s the beauty in skateboarding—that nothing is defined, so someone can come along and do things completely differently. In BMX there would have been a time when someone turned up to a competition with pegs, and was grinding instead of doing airs—and all of a sudden that changed the whole game.

But what the grades do I suppose is help to gamify it and make you come back. You come out feeling like you’ve succeeded—whereas that happens less with skateboarding. So there’s good and bad. We’re all still progressing—but it’ll be interesting to see what happens when we’re not still progressing. I think a big part of me skateboarding less was stopping to progress.

Yeah—people lose interest when the progression slows, so you’ve got to change something up.

Filip: Yeah—you’ve got to go somewhere new or something. As humans we seem to always want to find a reason to go somewhere.

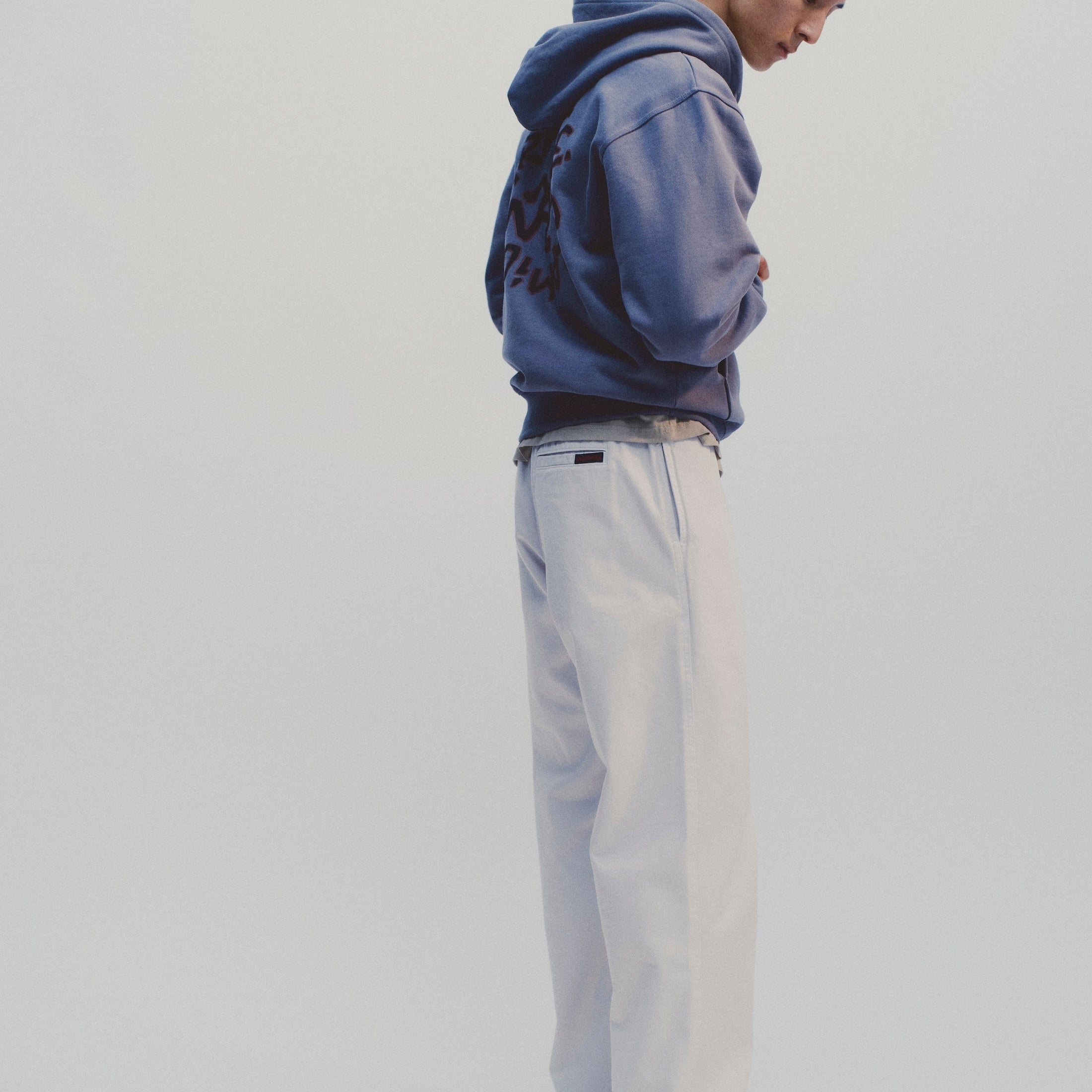

I suppose that brings me to these photos from Italy you took for Gramicci last year. Can you tell us a bit about that trip?

Alex: They were taken at a place called Val di Mello which is an hour or two north of Milan—it’s got these amazing granite cliffs, reminiscent of Yosemite. I went there with a friend of mine who’s also a photographer called Teo. I didn’t really know what was in store for us really—I hadn’t done any research—I’d just heard it was a destination for climbing, renowned for its bouldering festival. I thought there’d be multi-pitch sport routes, but there was actually a lot of traditional alpine style climbing where you’re having to put your own gear into the rock.

It was quite an intimidating place—you’re surrounded by these big granite cliffs, but we had a great time. In terms of a destination which is accessible—rather than go to Yosemite—it’s a great place. You can just fly to Milan, rent a car and you’re there.

Is it important to get out of your comfort zone a bit? It’s not like you only boulder or climb indoors.

Alex: Yeah, for sure. I think that this is a bit of a hangover from my dad, but with climbing for me there has to be a slight element of fear involved. That’s not the healthiest way of thinking about it, but I find it deeply satisfying. What’s exciting is that you never really have the same experience twice. You’re confronting these unique, idiosyncratic situations where you really have to think on your feet, thinking with your head and taking responsibility for yourself in a way that doesn’t happen in most of modern life. As much as I love going to the climbing wall, it’s a slightly sanitised experience—whilst if you’re walking up a mountain and then climbing it, you feel pretty responsible for your own life—and that’s kind of freeing or liberating in a way.

On the other hand, sometimes going climbing can be stressful, and I think why have I got myself in these situations? But that’s the beauty of climbing—you can also just go bouldering and have a more chilled experience.

Yeah—you don’t have to scare yourself all the time. I suppose we’ve talked for a while now. Before we wind this up, have you got any words of wisdom to end this with? Is there a Steep Learning Group motto?

Erik: Keep it vague. If you know what it is, it’s probably boring.

Find out more about Steep Learning Group here.