The humble climbing guidebook is a bit of an unsung hero of the outdoor world. These little books—made by climbers for climbers—offer vital information for anyone who wants to climb outside, crammed with routes, imagery and local knowledge that you can’t find anywhere else.

Even in an age of smartphones and high-speed internet, a well-researched guidebook thrown in a backpack is still hard to beat.

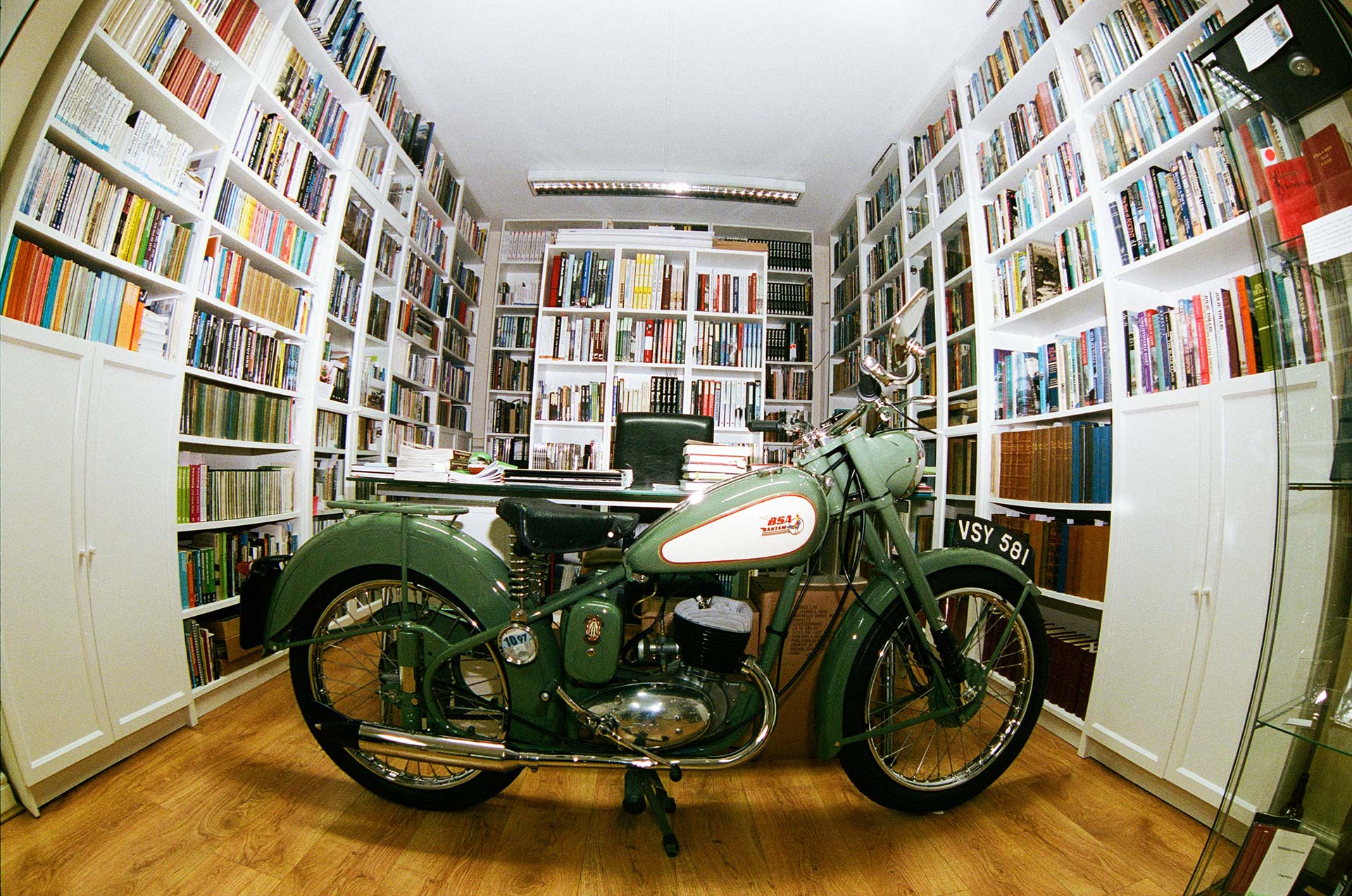

You might have already heard that we recently launched our guidebook library in our London shop, creating an information hub for those wanting to climb outside. Well, a good portion of the guides came from the collection of one man—David Price.

Not only is David quite possibly the most dedicated collector of UK climbing guidebooks, with a huge collection of seriously rare guides covering the whole of the British Isles, but he sells guidebooks, publishes guidebooks and makes his own guidebooks. In short, if you’re looking for a guide to guidebooks, he’s your man.

We paid a visit to his unreal collection to find out more…

Before we get to the guidebooks—how did you get into climbing in the first place?

I started climbing in my early 40s. I used to do a lot of cycling, but I found my upper body strength was going, so a friend of mine randomly said, "Do you fancy going to the climbing wall?” I really got into it, so I joined the Lancashire Caving and Climbing Club and a guy called Murray Gallagher took me under his wing. He’d always climbed, and he took me all over the show and taught me everything.

When did you start getting into the guide-books?

Initially I bought the current Lancashire guidebook—and that didn’t particularly get me into collecting guide-books. As a climber, you buy guide-books depending on where you want to climb, but then I got this book with these pen-and-ink drawings in it.

When I’d left school I went to work for my father at a plumbing and heating merchants, and I was doing pen-and-ink technical drawings. So when I saw these line drawings, I made the connection and that got me interested, so I started buying a few second hand guides, and it just went from there.

At one point I had one bookcase filled with books, and then I had some boxes on the floor, so then I bought a few more bookshelves, and then it just went on and on and on. But this is where it ends—you get people who have got books all the way up their stairs, but I’m not going there!

Haha—yeah, it’s important to know where the line is with this stuff.

I think you’ve got to have a cut-off point, but mine is quite an excessive cut-off point.

But like you say, your collection doesn’t extend out of this room.

Well, it does. I’m trying to make a bibliography of guidebooks, so I’m also interested in climbing guides in magazines and journals. A lot of magazines have climbing guides in them, and some of them are quite profound—so I’ve got a collection of magazines in the hall too. So if I ever get around to doing this bibliography—which is a massive job, then I’ll include the guides in the magazines too.

What do you mean by a bibliography—like a ‘guidebook of guidebooks’? That sounds like quite a task.

There have been three UK climbing guidebook bibliographies. In the latest one by Alan Moss there’s 1200 guidebooks in it, and that’s what I’d use when I was collecting. I had two identical copies of this book—because I’d take one out with me when I went to bookshops.

Ticking them off like an I-Spy book?

Yeah—exactly. And I’d note down which books I’ve got. But I had two identical, because if I ever left it in a bookshop, and I just had one, I’d be knackered! So that bibliography really is my bible, but it’s quite out of date, and over 200 guidebooks have been published since then, which is why I’d like to make a new bibliography.

The holy grail for collectors is what we’d call a ‘not in Moss’. That’s something that’s not in the Alan Moss book—so something that he missed. And I’ve found a lot. I bet between me and the other collectors that I know well, we’ve found 200—mostly things like home-printed guides or simple paper guides. I think because of the nature of things like these—because they’re just paper and people would take them out climbing with them, they’d get destroyed in their bag. So that means they’re really scarce. Some are just little pamphlets.

And this stuff was pretty DIY wasn’t it? I can’t imagine many copies of these simple printed guides were made.

They might have only made 50 of them. And that’s what I get excited about now. There are some books you’ll never get. Some of them, there might only be one copy still around. I accept that I’m never going to have every book out there, but I’ve got a very good friend called Nigel Baker who’s a climber and guidebook artist, and between me and him, we’ve got most of them. And it’s not about having every book.

They’re all different too—looking around it’s not like there’s a set way of making these things.

Yeah—everyone does things a different way. There are no set rules for guidebooks. Like the guide for those boulders in London which Steep Learning Group made—it might just be a fold-out sheet, but it’s still a climbing guide—and us collectors are fascinated with things like that.

Some of them are just single duplicated sheets—but they’re still guides, and they still might be really important, with climb names, descriptions, a topo and some history. I’ve got one made by Chris Craggs which was made in 1968 when he was still at school, and he only printed 12 copies. In the end I bought that off Chris himself—it was his copy.

Even now, even with smart-phones and the internet, people are still making guidebooks, and climbers are still using them. Why do you think they’ve stuck around?

I remember maybe seven or eight years ago, a collector said to me, “There won’t be any guidebooks in five or ten years, they'll all be online” How wrong. People like physical books. It’s awful looking at your phone or a Kindle. There’s nothing like looking at a book—when you open a new book and it smells of ink—there’s just something about it you can’t replicate—it’s a physical thing.

And when you’re climbing in the middle of nowhere, a book is a lot more reliable.

Exactly. Books are just fantastic. That book that Chris Craggs wrote in school is 56 years old now, and you can still read it now.

Your collection sort of shows the history of these guides over the last century. How have these things changed over the years?

I suppose the big change was going from pen and ink line drawings to photo topos. I’ve tried to keep line drawings alive—so a lot of the guides that I publish will have drawings by Malc Baxter in them—a guide-book artist who has been illustrating guides for over 60 years.

"There’s nothing like looking at a book—when you open a new book and it smells of ink—there’s just something about it you can’t replicate—it’s a physical thing."

The illustrations are so much nicer, and from a practical point of view, the drawings do a better job because you can emphasise features. Virtually all of the guidebook artists were climbers—and good climbers too—and they knew what features were important and what wasn’t. So I think the illustrations are better, but they’re not used as much now because of how time consuming they are. They’re just not practical in this day and age, but I think they’re a lot better, and much more pleasant to look at. It was around the mid-90s when illustrations started dropping off.

There’s trends or shifts in printing too over the years—it’s the same with zines or magazines and how you can kind of date things by how they were printed. Was there a heyday for the guidebooks when you think they were at their peak?

That’s a hard question to answer, because at different times, different elements really shone. There’s no question that the overall quality regarding guidebooks is in a different league to the 70s and 80s. Rockfax have got it down to a tee. But then there are so many privately published ones too—it’s a big job to put a guidebook together, but it’s relatively easy now with digital printing and print-on-demand.

Is that the beauty of them? They’re made by passionate climbers, not someone trying to make money.

Exactly. There’s a lot of love that goes into these books. There are exceptions, and some of the bigger companies produce guidebooks to make money—but yeah, I didn’t spend seven months creating my guidebook to make money. I actually worked out how much I made on that, and it was something like 12p an hour! These things are real labours of love, which does make them very special.

I imagine the hunt is a big part of this. These books aren’t the kind of thing you can easily buy on the internet.

Yeah—I used to spend a lot more time searching things out, but now I’ll get someone emailing me maybe once a week—coming to me with their collection, and seeing whether I’d be interested in buying it off them. And that’s where a lot of the really rare stuff came from. I used to spend a lot of time going around second-hand bookshops, but it’s very rare I’ll find something in them now that I haven’t got. But you’re never going to get every guide-book—there’s always another one out there. It’s endless.

Are these things expensive?

If you collect narratives—like non-fiction books about expeditions—you can pay a lot of money, but collecting guidebooks is relatively cheap. You can pick them up from second-hand shops for a few pounds. However, I’ve paid a lot of money for some guides, simply because I knew I won’t find another.

Even old duplicated sheets—because of the nature of them, not many survived—I might pay £100 for something like that, even though they’re just bits of paper. I wouldn’t like to add up how much money I’ve spent—especially with all the original drawings I’ve got. But you can’t put a price on this stuff—things like guides with letters from the author, or a book that’s been owned by a famous climber, with their annotations inside—how would you put a price on that?

Is your collection almost a way to preserve all this climbing knowledge—to keep it from getting thrown away?

Yeah—I had an email the other day from an old boy who was getting rid of his guidebooks, and in my reply I said that I was particularly interested in UK climbing guidebooks, and the ones that have real value are often just duplicated sheets or pamphlets—and not to throw any away.

I once bought some guidebooks off a guy in Preston. His house was immaculate, he was immaculate and his books, even though he’d been using them as guides, were immaculate. I bought something like 20 books off him—all in really good condition. And I said, “Oh, you’ve got no duplicated sheets or pamphlets have you? He said, ‘Why?” I told him that they were the ones that could fetch £100 sometimes, and his jaw dropped. He’d thrown them all away because he didn’t think anyone would want them.

I’ve found them folded up in other books before. Most people don’t even know they’ve got them. When someone passes away, the hardback books go on eBay because they look quite good, but the sheets just get thrown away. And that happens, even though they’re the really hard things to find.

How do you keep a handle on this? There’s quite a fine line between a healthy pastime and something that takes over your life?

You’ve just got to keep a perspective on it. I’ve been really disciplined in making sure I’ve not got books all over the house. I kept a physical limit on what I could collect, and that’s a really good measure. I’ve got lots of other interests, and although this is a very big interest—and you might think it’s the be all and end all for me, it isn’t. Let’s say my house burnt down, I wouldn’t try and start collecting them all over again.

Did you have that collector mindset as a kid—collecting comics or toys or anything?

Possibly, to a degree. I think as a kid you can only do so much collecting, but I’ve always been the kind of person who doesn’t do things by half measures. People will say of me, “It doesn’t matter what you do, but you always do a really thorough, proper job.” And that goes back to my father, because he drummed into me that you always do your best, so if I’m doing something, I’ll do a very thorough job—as well and as conscientiously as I can. It doesn’t matter what I’m doing, but I always try. And it takes some energy that—to keep that up all your life.

I can imagine. A lot of people are quite happy to dip into things—but for you do things get richer the further you go with them?

Yeah—I like knowledge, so the more you collect the more you know. I don’t know everything about these books, but I’ve got a lot of knowledge now about UK climbing.

This is usually a tough one to answer for collectors, but do you have a favourite guide?

I thought you might ask me that—but that’s impossible to answer. I’ve got a few—and for different reasons—whether it’s the scarcity or the story. That Chris Craggs book for example—when I first approached him to buy it off him, I asked if he’d allow me to do a reprint as well. He typed it all up, and we kept the typos and everything still in, exactly as it was—but me being me, I wasn’t happy at that, so I taught myself how to case-bind books, and made ten case-bound copies. And that, because of the story, is one of my favourite guides.

When I think of my favourite guides, it might not be what I think is actually the ‘best guide’—it’s actually the story behind it.

On the other hand, what makes a good guide for someone who’s climbing?

Well, you’d just have to look at the modern guides. A lot of the privately published guides are great too—even something like the little supplements can be so well put together, and they might only get 100 of them printed.

But yeah, you won’t go far wrong with the Climbers Club guides or Rockfax. And there’s a guy called Steve Broadbent—he’s a clever bloke—and he produces these books under the name ‘The Oxford Alpine Club’, and they’re really, really good.

You’re not just a collector, but you also publish guidebooks yourself. Does making your own guidebooks give you a newfound respect for the network of people who’ve made all these over the years?

Without a shadow of a doubt, My guide, Selected Climbs and Bouldering in Wilton Quarries—even though there’s very little new information in there, I spent seven months on that, more or less full time. You’ve got to be multi-skilled to do a decent guidebook—there are so many elements, from photography to topos to descriptions to writing—and then there’s the research and the checking over everything. There’s not just one element to them. But I like a challenge like that—I’m not the best writer in the world—but it’s something I enjoy doing.

Rounding this off, what’s the buzz from collecting something like this? Is it the books themselves, or the hunt, or something different altogether?

The best thing about collecting the guidebooks isn’t the books on the shelves, but the people I’ve met. Yeah, I like the books—I’ll sit for hours reading them—but I can’t start to list the number of amazing people I’ve met through this. The number of authors and artists and collectors just goes on and on. The books are great, but it’s really the people.

Find out more about David's collection here.